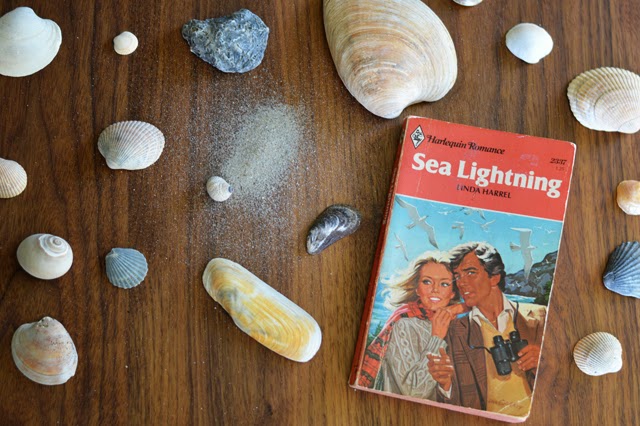

So if you read yesterday’s post on my Utterly Unscientific Summer Saturday Series Sex Survey, you know that today I’m going to be writing about Sea Lightning by Linda Harrel, a Harlequin Romance published in 1980, but originally put out by Mills & Boon in 1979. One note: when I say Harlequin Romance, I’m referring to the specific line at Harlequin, not a general term for romances or even a general term for Harlequins. Throughout this survey, if it’s capitalized, it’s the name of the line.

First, a little bit about Harlequin. I’m no kind of expert, but here’s what I’ve been able to garner from Wikipedia and various romance bloggers. While Harlequin as a company started in 1949, their partnership with Mills & Boon, a British publisher of romance novels, didn’t start until 1957. My understanding is that Mary Bonnycastle, the chief editor at Harlequin, had a real resistance to printing the more sexually explicit material found in some Mills & Boon titles and would reject reprinting books that didn’t meet her decency standards. Here’s what I don’t know: how long did that control last? And what lines did it cover? I’ve got a hold on Pamela Regis’ book A Natural History of the Romance Novel at the library, but it hasn’t come in yet. I have to get the Joseph McAleer Mills & Boon history from interlibrary loan so that will likely take longer.

My personal experience with the Harlequin Romance line has been mostly kissing with the occasional breast grope all the way up through the late 1970s. The Harlequin Presents line, which started in 1973, I understand is slightly sexier, with Anne Mather, Charlotte Lamb and Violet Winspear particularly having the reputation for books that run toward more sexual tension. But the actual sex acts depicted in the ones I’ve read have been limited to vague allusions to sex after marriage–basically the romance novel equivalent of television’s “one foot on the floor” Hays Code. We get wives in nighties and perhaps some vague post-coital cuddling, but no actual sex, certainly not in the way we’ve come to expect as modern Presents readers. I’ve only read about a dozen of each of these lines though from the time period I’m covering now (my reading in the past has run to older titles) and never made a careful or chronological study of them so that’s what I’m interested in exploring this summer.

Sea Lightning by Linda Harrel is a good place to start because it’s pretty typical of the earlier Harlequin Romances I’ve read. Heroine Jensa Welles is a professional illustrator sent to Argentina by her former teacher and mentor to work with marine biologist Adam Ryder on a scientific book of whale behavior and migration patterns. Right off the bat, we get straight to the reason I so love these older category romances. On page 28 & 29:

‘I shouldn’t think you’d be bothered by much human company no matter where you lived–you’re not exactly welcoming yourself, you know,’ she muttered, holding on to her seat for dear life.

‘I could be…if I take into account the purely decorative advantages of your presence.’

The suggestiveness in his voice stiffened Jensa’s back and sent a slight prickle running down her spine. She turned her head to one side and stared out at the broadening desert. He was still trying to unnerve her. And she had to admit that he was very close to succeeding.

…

Jensa caught her breath and felt her eyes widen.

‘You’re an overgrown child, Adam!’ she snapped. ‘You think all this

bluffing is going to panic me, providing you with some petty,

small-minded amusement.’

Not only has Adam called into question her professional competence by this point (purely on the basis of her sex–and says so outright), he has ordered her to return home, threatened her with the primitive conditions at the research station, made suggestive comments about her appearance and now these more overtly sexual threats. It’s textbook sexual harassment, almost a caricature it’s so bad. And it continues through much of the book. As a modern reader, it’s unpleasant, jarring and offensive. If it occurred in a contemporary romance novel today, it would likely get an automatic trip to DNF-land from me except for one thing: Jensa stands up to him, verbally protesting his language and behavior. He doesn’t change it, but she said something, which is pretty brave considering he already doesn’t want her there and she basically has no recourse, legal or otherwise.

Now for the sex. There isn’t any. I wouldn’t even call the novel particularly thick with sexual tension. It’s more thick with Adam wanting, Jensa denying and feeling quite guilty and embarrassed when she does find herself experiencing desire. Adam makes several references to the fact that since Jensa is a beautiful woman, she must have quite a lot of sexual experience, for whatever beauty has to do with desire or promiscuity. For example:

With that cynical announcement, he leaned his body over her and pressed her back on the sofa, covering her mouth with his, brutally forcing it open. When at last he finally released her, he said, ‘I did that to shut you up–you push me too hard, you know.’

He withdrew his body from hers, leaving her shaken and unable to reply. But when she looked up into those cold, mocking eyes, her response came in full. She brought her hand across his face with a sharpness that drew colour to his cheek and pain to her hand.

His hand flashed out and caught her wrist, pinioning it to the seat. ‘An appropriate reaction, Miss Welles, and well done. But I know women who look like you love such attention…even though they all feel obliged to go through with these little charades of mock outrage.’

There isn’t a single word in those paragraphs that isn’t horrifying to this modern reader. He physically restrains her. He kisses her against her consent and does so to shut her up. Nor is it a gentle kiss. He’s condescending about all of it. Finally, he makes the ridiculous assumption that beautiful women desire that kind of sexual attention, but want to make him work for it. If anyone needs a primer on how rape culture works, this is pretty much it. Oddly though, Adam has a fairly veiled sexual relationship with an Evil Other Woman in the novel, but she remains largely unjudged for her behavior. One assumes that beautiful women who conform to his sexual expectations are excepted from his wrath.

Of course, Adam hasn’t really had a female role model in his life. His high-flying society mother left his dull, dreary, scientist father when he was very young. This seems to be held up as an explanation for his behavior, but also a the main sticking point in his personal development as human being. It’s quite Oedipal really. Jensa suggests at one point that he should consider reconciling with his mother, which he eventually does, off-stage. And after that, his behavior changes. There’s an ethos that even now permeates some romance novels: that the savage, uncontrollable male is tamed by the love of his heroine. That’s not quite what happens here, not directly. At least, the change to his behavior seems to come from reconciling with his mother, though of course it’s at Jensa’s suggestion.

Toward the end of the novel, Adam’s gives Jensa full credit for her contribution to both his conference presentation and an enormous win in

his efforts at whale habitat conservation. Though they part on bad terms shortly before the end of the novel (yes, of course they get together

in the end), Adam includes Jensa’s business contact information on his conference materials even though he isn’t obligated to. He and other men

are depicted as having quite a lot of respect for her professional abilities. It was just as satisfying for me as a reader that Jensa earns

professional respect in the end as it was that she earns the sexy scientist’s love.

There’s some more fairly uncomfortable kissing that ranges from violent and expressly unwanted by Jensa to merely forward and only reluctantly abandoned by Adam (a total of four at my count). And yet, the last kiss in the novel tells a different story.

He looked at her expectantly. Slowly, tentatively, he reached out to her again, and this time she did not resist. ‘I love you, Adam. I love you so very much,’ she whispered as he pressed her to him. He kissed her then in that way that brought her breath in short, exquisite gasps.

…

He brought her to him once again. There was silence in the room for long moments after that. Finally, as Adam withdrew his lips from a hungry caress of her neck, he whispered, ‘You and I must go and do that sightseeing. A hotel room is decidedly not the place where we should be right now! Our time will come–and soon, my darling.’

Yes, she thought, looking up at hi in wonder and in joy. She knew that neither he heart nor her body had betrayed her, after all, in urging her to love this man. With him, she would be safe and cherished, always.

So here’s the thing: despite Adam’s horrific attitudes early in the novel and the brutal kisses he inflicts on her (which of course she sort of likes even if she’s loath to admit it even to herself), Sea Lightning was quite a good novel. Even though Adam’s redemption happens very quickly, it’s sufficiently complete (and has the additional factor of reconciling with his mother) that I actually sort of believe that they might really be alright together. There’s also an amusing discussion of potential future children and how Jensa will continue to work while the kids are educated in a very the-world-will-be-your-classroom manner.

In other words, Sea Lightning answers both sexual and professional questions for women in ways a modern reader, thanks to a broader acceptance of feminist principles, would never even think to ask them. While the perspectives on sex aren’t modern ones by a long shot since the “loose woman” doesn’t get the guy and the virtuous heroine does, and Jensa feels guilty about any desire she experiences throughout the novel, at least by the end the hero is respecting her sexual boundaries and acknowledging her professional competence.

I’ll be reading in chronological order throughout the summer so the next book on the list is Charlotte Lamb’s Possession, a Harlequin Presents from 1979. Let’s see if changing lines makes any difference to social mores or sexual content.

And don’t forget that readers can contribute to both my 2U5S spreadsheet in a public Google doc and the link party on the 2U5S main page. Come, share the old category love.

May 23, 2015 at 8:47 pm

"There's also an amusing discussion of potential future children and how

Jensa will continue to work while the kids are educated in a very

the-world-will-be-your-classroom manner."

I did a little bit of research into Sea Lightning when I was writing For Love and Money: The Literary Art of the Harlequin Mills & Boon Romance and I concluded that Harrel must have drawn heavily on an article National Geographic about whales off the coast of Patagonia. The author explains how he took his whole family with him, and how great it was for the children, which I think probably explains how/why that element of the ending was created.

May 26, 2015 at 12:01 pm

Now why did I think that wasn't coming out until later this summer? Well, I have it now. I didn't expect to want to dig into the scholarship on this, but at some point I'm going to have to. My plan of reading just the books I already have in my possession is proving unsatisfying. I want definitive answers.

Anyway, very interesting about the National Geographic article and Sea Lightning. The detail about future children did seem a peculiar thing to stick in there at the end. Not out of character necessarily, just unusual and highly specific. But yes, that does seem a good explanation.

May 26, 2015 at 8:51 pm

I once had an early M&B, from the 1920s or 1930s, in which I think the hero got the heroine pregnant and they weren't married. She left him, taking the child with her and I think only agreed to marry him some years later, after she'd become a famous author. Unfortunately, I just skim read it and then, when it turned out I didn't need it for my book, passed it on to an academic library which was collecting popular fiction. I've got another one in which (again, I've only skim read this, but it was from the same period), the heroine ends up on the run to try to save a child from being sexually abused by its father/step-father. I don't recall either McAleer or jay Dixon's book on M&B's mentioning those storylines but, unfortunately, my memories are vague enough that I worry I'm getting something wrong.

I'm not sure either were very explicit in terms of the sex scenes, but it makes me feel they covered more controversial topics than one might perhaps expect. But in the 1920s and 1930s, I don't think M&B had quite settled into specialising in what we'd now called romance, so maybe that had an effect on the kinds of storylines which were deemed acceptable then. Also, they were relatively fat books, much fatter than the later category romances.

June 7, 2015 at 3:02 pm

That's very interesting. I wonder if those were being marketed specifically to women yet? And if the storylines changed with the marketing? The more I read, the more I realize how little I know about the history of the genre. For instance, one of the books I found this weekend was a US-published book called "Graduate Nurse" from 1956 which has a super pulpy cover and seems to feature three guys fighting over one woman. The cover copy seems centered around her, but I'm not at all sure if it was intended as titillation for a male market or whether it's just more open-minded than later books? Guess I'll have to read it and find out.

June 7, 2015 at 3:09 pm

"The more I read, the more I realize how little I know about the history of the genre." – I feel the same way. There have been so, so many romances published that even an avid romance reader can barely scratch the surface and there's been relatively little secondary work published about them.